MATTI STURT-SCOBIE

Review

28/11/2023

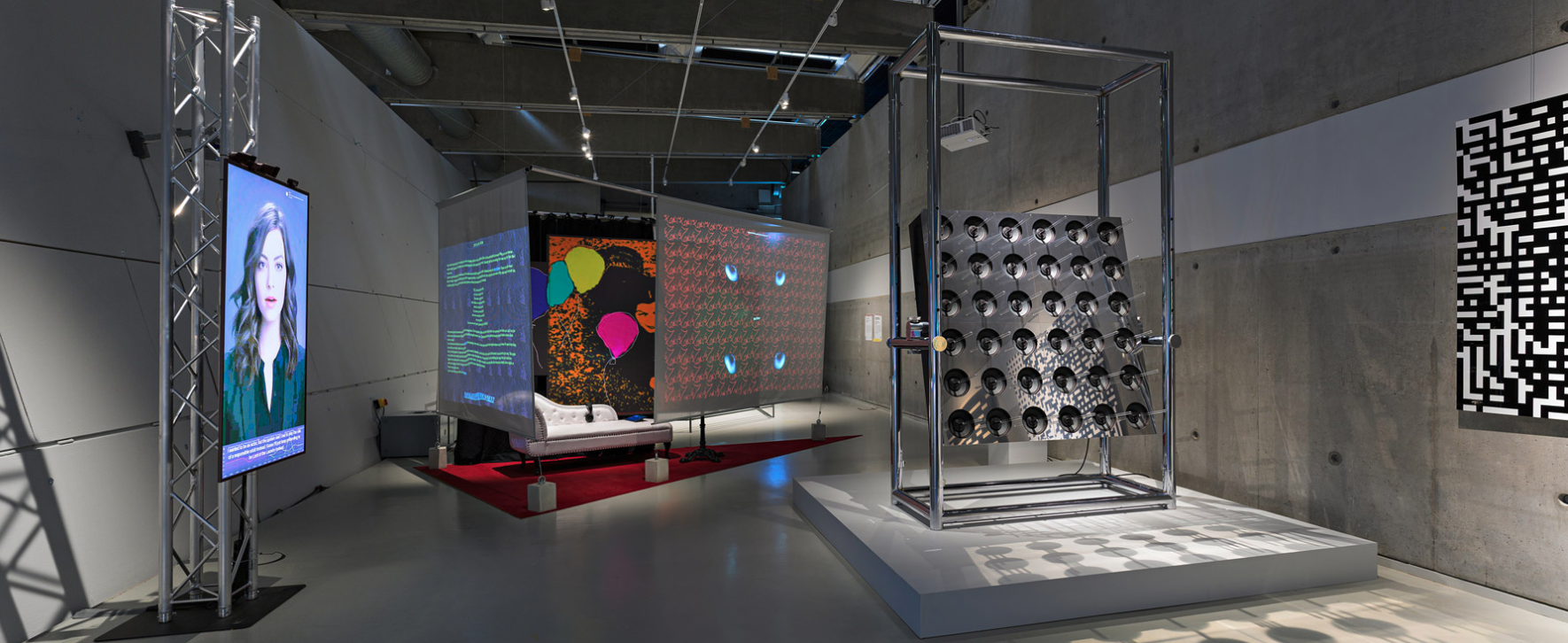

Overview 'REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art', Nieuwe Instituut icw Li-MA. Photo: Pieter Kers, Beeld.nu

Between 8-Bit and 8K: visiting 'REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art'

HET NIEUWE INSTITUUT, Rotterdam

WEBVIEW

Will art made of outdated tech continue to bear intrigue for modern audiences? Matthew Sturt-Scobie visits the ambitious exhibition REBOOT at Nieuwe Instituut, made in collaboration with media art platform Li-Ma. It presents key technology-driven artworks from 1960 to 2000 alongside contemporary digital art.

Artists

Annie Abrahams, Livinus and Jeep van de Bundt, Driessens & Verstappen, Edward Ihnatowicz, JODI, Bas van Koolwijk, Lancel/Maat, Jan Robert Leegte, Yvonne Le Grand, Peter Luining, Martine Neddam, Marnix de Nijs and Edwin van der Heide, Dick Raaijmakers, Joost Rekveld, Remko Scha, Jeffrey Shaw, Steina, Peter Struycken, Michel Waisvisz and with contemporary responses by Janilda Bartolomeu, Cihad Caner, Dries Depoorter, Swendeline Ersilia, Ali Eslami, Jonas Lund, Luna Maurer and Roel Wouters, Play the City and Brui5er,

Standing at the maw of REBOOT, an exhibition at Nieuwe Instituut, made in collaboration with media art platform Li-Ma, a throbbing, dark and percussive droning calls from within. The space sits somewhere between contemporary loft apartment and mission control bunker. Amidst these concrete walls and shifting audio elements lies the Dutch 'Digital Canon', a vast body of technology-driven artworks made in the Netherlands between 1960 and 2000. Alongside, nine contemporary artists have created works in response. ‘In dialogue with each other’, the exhibition text states, ‘they will illustrate how digital technology has entered the capillaries of society, how incredible innovations are becoming commonplace at an ever increasing rate’. An interesting set-up, that presents the curators with a challenge: will the visitors be able to traverse the chasm that opens between 8-Bit and 8K? Will art made of outdated tech continue to bear intrigue for modern audiences?

I approach the first to find out: three abstract, geometric paintings titled Computer Structures (1969-1972) by Peter Struycken. Struyckens’ paintings are outcomes, dictated by a program from the dawn of digital time, when computers were the privileged tools of tech-laboratories. Struycken would use the program to designate the proportions and elements within his work ‘at random’ (in quotes as he would later select his favourites). The outcome of these particular works is that of a patterned spread, akin to the pixels of a highly zoomed image. Because the technology used has long-since shed any ‘cutting edge’ glamour it might have exuded – I’m left pondering the artistic value of the works as paintings, were they not computer generated; whether through more dynamic presentation or environment, they could be re-encountered beyond their historicity. The works certainly carry historical significance, but in their new 'commonplace' state, they become fossils through contemporary eyes.

I approach the first to find out: three abstract, geometric paintings titled Computer Structures (1969-1972) by Peter Struycken. Struyckens’ paintings are outcomes, dictated by a program from the dawn of digital time, when computers were the privileged tools of tech-laboratories. Struycken would use the program to designate the proportions and elements within his work ‘at random’ (in quotes as he would later select his favourites). The outcome of these particular works is that of a patterned spread, akin to the pixels of a highly zoomed image. Because the technology used has long-since shed any ‘cutting edge’ glamour it might have exuded – I’m left pondering the artistic value of the works as paintings, were they not computer generated; whether through more dynamic presentation or environment, they could be re-encountered beyond their historicity. The works certainly carry historical significance, but in their new 'commonplace' state, they become fossils through contemporary eyes.

Peter Struyken's digitally designed paintings certainly carry historical significance, but in their new 'commonplace' state, they become fossils through contemporary eyes.

Peter Struycken, 'Komputerstrukturen' (1969-1972). On view at 'REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art', Nieuwe Instituut icw Li-MA. Photo: Pieter Kers, Beeld.nu

Overview 'REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art', Nieuwe Instituut icw Li-MA. Left: Jan Robert Leegte, 'Scrollbar Composition (2000), right: Jonas Lund, 'Why did the self-referential artwork hire a comedian?' (2023). Photo: Pieter Kers, Beeld.nu

In contrast, the work Scrollbar Composition (2000) by Jan Robert Leegte, seems well enough alive. The work is a website, for now ‘alive’ so long as it is hosted by a service provider. Though each (web)site is the same code and the same tessellations of blue planes framed in the eponymous scrollbars – it adapts to new web browsers and the anatomy of the monitor that houses it. Because of this, the curatorial decision to present it on three Mac computers from distinct eras revives the work: rigid antique grids evolve to smooth rounded lines that vanish when not in use, their blue hues subtly varying. An ant farm of sorts, these scrollbars jitter and writhe, bound to their 90 degree axes. Slowly, they’ve devoured their housing – cumbersome, off-white plastic is eaten away revealing slim bones of glass and aluminium. There is a new narrative here, clunky desk furniture disappearing into ergonomic, user-friendly extensions of the body – the membrane between us and cyberspace thinning. Next to Computer Structures, it becomes an important demonstration of how scenography can defrost or defibrillate more ‘dated’ works.

Following this, I encounter the first of the ’artistic responses’, the first conversation between old and new: Why did the self-referential artwork hire a comedian? (2023) by Jonas Lund, which answers Ideofoon I (1967-1970) by Dick Raaimakers. Lund’s work is a series of CGI talking-heads, some strangers, others cultural figures. Through uncomfortable, purposeful eye contact and awkward approximations of human mannerisms, they become eerily uncanny creatures. These talking-heads tell “jokes” that come across as AI-generated, chimerical word-salad. Supposedly, cameras above them monitor your facial expressions so they might learn how to capture your attention more effectively. Whilst unsettling, there’s no real sense of process – we’re left to trust that there is something interesting going on behind the screen. Here, the relationship between the two artworks is tenuous, strung by the finest thread that they are both a feedback loops of sorts.

In these creatures line of sight stands Ideofoon I, made up of 36 loudspeakers, mounted together in the form of a rectangular cube that then rotates on its axis. Cylindrical glass tubes containing steel balls are mounted at the centre of each speaker. As it rotates, the silver spheres roll and trampoline upon the speakers’ surfaces, each moment of contact causing a short-circuit in the system that generates a pitter-patter of rain-like clicks. The work becomes a self-playing instrument that is both input and output – a series of intentional, mechanical glitches that (compared to Lund’s work) simply and effectively reveal the inner-workings of the system. Awkwardly, since Ideofoon I is so succinct and intelligible compared to Lund’s work, the dialogue quickly becomes whether more advanced correlates to more impactful.

Following this, I encounter the first of the ’artistic responses’, the first conversation between old and new: Why did the self-referential artwork hire a comedian? (2023) by Jonas Lund, which answers Ideofoon I (1967-1970) by Dick Raaimakers. Lund’s work is a series of CGI talking-heads, some strangers, others cultural figures. Through uncomfortable, purposeful eye contact and awkward approximations of human mannerisms, they become eerily uncanny creatures. These talking-heads tell “jokes” that come across as AI-generated, chimerical word-salad. Supposedly, cameras above them monitor your facial expressions so they might learn how to capture your attention more effectively. Whilst unsettling, there’s no real sense of process – we’re left to trust that there is something interesting going on behind the screen. Here, the relationship between the two artworks is tenuous, strung by the finest thread that they are both a feedback loops of sorts.

In these creatures line of sight stands Ideofoon I, made up of 36 loudspeakers, mounted together in the form of a rectangular cube that then rotates on its axis. Cylindrical glass tubes containing steel balls are mounted at the centre of each speaker. As it rotates, the silver spheres roll and trampoline upon the speakers’ surfaces, each moment of contact causing a short-circuit in the system that generates a pitter-patter of rain-like clicks. The work becomes a self-playing instrument that is both input and output – a series of intentional, mechanical glitches that (compared to Lund’s work) simply and effectively reveal the inner-workings of the system. Awkwardly, since Ideofoon I is so succinct and intelligible compared to Lund’s work, the dialogue quickly becomes whether more advanced correlates to more impactful.

Cylindrical glass tubes containing steel balls are mounted at the centre of each speaker. As it rotates, the silver spheres roll and trampoline upon the speakers’ surfaces, each moment of contact causing a short-circuit in the system that generates a pitter-patter of rain-like clicks

Dick Raaijmakers, 'Ideofoon I' (1968), from the collection of Kunstmuseum Den Haag. On view at 'REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art', Nieuwe Instituut icw Li-MA. Photo: Pieter Kers, Beeld.nu

Yvonne le Grand, 'La Zoyd’s Pataverse' (1996-1997). On view at 'REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art', Nieuwe Instituut icw Li-MA. Photo: Pieter Kers, Beeld.nu

Following Ideofoon I, we’re invited to enter Yvonne le Grande’s blog-come-boudoir titled La Zoyd’s Petaverse (1996 - 1997). This work provides the audience’s introduction to the early web’s cyberfeminist movement. Unfortunately, the presentation seems low-effort and there’s little content to engage with. Inside, sits a white chaise longue and a plastic wine glass filled by neon yellow fluid. From a tablet computer (mess of wires on full display), you can listen to two audio works: monologues on the cultural significance of avatars, sewn with autobiographical elements – in their backgrounds play baroque pop tracks and synth arpeggios. Though I found these works somewhat engaging, I felt disappointed – denied the opportunity to fully submerge myself in the world inferred: an excited world of mystery, anonymity, intimacy and storytelling, free from hetero-patriarchy.

One of the many texts scattered throughout Nieuwe Instituut states: ‘Artists explored how identity could be reshaped in this virtual space. A striking number of female artists took a progressive stance on the internet.’ Indeed, I discover that most of the legacy women-artists presented at REBOOT made internet art created within this territory, on and for the world wide web. It’s no secret that such artworks (alongside ephemeral artworks, public interventions, land art and many more) present a curatorial hurdle. As aliens to the gallery format, better habitats or atmospheres were needed for these works to breathe, in their new hostile ecosystem. Which is a shame, since Scrollbar Composition did this so well.

There is one extra notable screen based saving grace: Ali Eslami’s Homā’s Phantom (2023). Within it you sit, fighter-jet joystick in one hand, red scrolling-ball in the other, sceptre and orb, as if leading some esoteric ceremony. In front of you, a highly polished, explorable 3D render of a sandstone labyrinth. Within, the rules of how one experiences space and time are warped. You encounter mysterious quasi-religious totems and hidden glowing messages whilst a light rain trickles from clear skies. These elements together create a powerfully immersive, surreal world – the most true-to-life analog for a dream I have ever encountered.

Other works of note include Spatial Sounds (100dB at 100km/h) (2000) by Marnix de Nijs and Edwin van Der Heide. This work is made of a trebuchet-like construction of steel mounted with a loudspeaker that propels itself in a vicious spin (around 100km/h I assume). Emitting the deep, percussive groan of a motorbike engine, it spawns a visceral response within you, an anxiety that violence is near. Further, Emoji is All We Have (2023) by Luna Maurer & Roel Wouters provides a humorous, but also beautifully staged video work set in the Swiss alps, exploring (with a bright levity) the network of impacts emojis impart on human connection.

Ali Eslami’s Homā’s Phantom (2023) is the most true-to-life analog for a dream I have ever encountered

Ali-Eslami, 'Homā's Phantom' (2023). On view at 'REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art', Nieuwe Instituut icw Li-MA. Photo: Pieter Kers, Beeld.nu

Luna Maurer & Roel Wouters, 'Emoji is all we have' (2023). On view at 'REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art', Nieuwe Instituut icw Li-MA. Photo: Pieter Kers, Beeld.nu

Marnix de Nijs & Edwin van der Heide, 'Spatial Sounds' (2000). On view at 'REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art', Nieuwe Instituut icw Li-MA. Photo: Pieter Kers, Beeld.nu

I mention these to insist that there are resonant works within the exhibition, but they often tread water in a sea of noise. REBOOT’s approach is aggressive and overstuffed, seeking to house what seems like the totality of Dutch new media art history alongside a further nine contemporary responses. All the while, we’re asked to interpret this mass through four separate given narratives. I’ll loosely describe these as: identity online, computer aesthetics, online power structures and human collaboration with machine. We are reminded throughout the exhibition (with colour-coded tape) which storyline each work could belong to. This initiates a tiresome game of decoding each colour’s meaning and re-referring to the appropriate text. Further, as the chasm opens between older works and new, they indeed illustrate “how incredible innovations are becoming commonplace at an ever increasing rate.” To me, this seems a peculiar goal. It highlights what the dated works now lack in impact or affect – made aware that the potentialities we might have felt in their time having long since evaporated. I would like to have seen more effort made to resuscitate them.

The exhibition, in places, relays to us early artists’ proclamations that computers would free us from human bias, engendering a future of untethered creativity. If there’s one thing the exhibition does well, it is capturing this fanatical optimism. Though, in their own enthusiasm for the body of work Nieuwe Instituut seems to have resisted selectivity or concise narrative – becoming a tangle of roads taken all at once.

REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art is on view until April 1st, 2024

The exhibition, in places, relays to us early artists’ proclamations that computers would free us from human bias, engendering a future of untethered creativity. If there’s one thing the exhibition does well, it is capturing this fanatical optimism. Though, in their own enthusiasm for the body of work Nieuwe Instituut seems to have resisted selectivity or concise narrative – becoming a tangle of roads taken all at once.

REBOOT: Pioneering Digital Art is on view until April 1st, 2024